Manic Street Preachers Discuss New Album

Manic Street Preachers have spoken to NME about their song ‘Dear Stephen’, inspired by Morrissey, the road to their new album ‘Critical Thinking’, and how they’re already contemplating their next move.

- READ MORE: Manic Street Preachers – ‘Critical Thinking’ review: former generation terrorists shoot hope through doubt

Released today (February 14), the Welsh rock veterans’ acclaimed 15th album was said to be born of “eternal uncertainty, doubt and desire.” Bassist and lyricist Nicky Wire told NME how that allowed for “a different kind of record” than what might have been expected from the Manics before.

“Albums are a reflection of where your mind is at – certainly in the Manics’ world,” said Wire. “Sometimes you have to let that honesty out. I just went off myself a bit, but I always find myself to be my most dependable source of inspiration. I’m starting to lose that – but that’s different from the lyrics from James (Dean Bradfield, frontman) on the album; his three songs have more of a sense of optimism to them.”

Exploration and Reflection in ‘Critical Thinking’

Around the release of 2022’s ‘The Ultra Vivid Lament’, Wire described the predecessor album as an “exploration of internal galaxies” that saw him “digging deeper into himself” and “on the retreat.” The Wire-sung opening title track ‘Critical Thinking’ – described by NME as “a snarky diatribe spitting back at the false empathy in social media’s conveyor belt of empty platitudes” – seems to have Wire taking a more assertive stance once again.

“The only thing I attack on this record is myself,” he told NME about ‘Critical Thinking’. “The moral judgement on this album is very much the mirror, maybe with the exception of ‘People Ruin Paintings’ which is a bit broader. ‘Critical Thinking’ the title track conveys a different kind of lyrical nastiness and is very much a warning to the self: the notion that the brain is just as important a muscle as any other. You have to go to the gym for the mind, which for me was simply writing it all down and aiming for different perspectives.”

“I know it sounds really nihilistic and narcissistic; it’s just the way it was. We don’t have time to truly interrogate what kind of album we want to make or how we do it.”

Bradfield, meanwhile, told NME how having “no real mission statement” or concept for ‘Critical Thinking’ granted the band “a sense of freedom.”

“As you get older and as all the concepts, ideologies and understandings that you’ve grown up with start to dissemble and crumble around you – whether it be left, right or left of centre – once you realize that they become a separate tense and economies work in different ways – the game is up,” said the frontman.

“You can’t think the way you used to think. You’ve got to have a looser way of thinking and see what comes out of it. That’s what we did with this record.”

Bradfield highlighted the opening title track alongside the aggressive closer ‘OneManMilitia’ (also sung by Wire) as the extremes of the album.

“They’re two songs that rage in a very Nicky Wire-esque way, they’re lyrics that stand alone,” he stated. “They don’t seek empathy, they don’t ask for support, they don’t require your agreement; they are what they are. He’s done that many times before but even better this time.”

“Those songs are cohesive, but then you’ve got ‘Hiding In Plain Sight’ which is the polar opposite and very empathetic towards himself; it’s asking to be listened to in the right way. ‘Decline & Fall’ connects with us and the world we inhabit. It articulates where we stand and how we feel. It doesn’t indulge in self-pity; it simply narrates how it is.”

At the heart of the album is ‘Dear Stephen’ – inspired by a postcard sent to Wire as a teenager from Morrissey at his mother’s request after he was too ill to attend a Smiths concert.

Many reviews of the album and fan commentary have assumed that the line “Dear Stephen, please come back to us” is a plea for Morrissey to return to his ‘80s prime, prior to the controversies that have surrounded him in recent decades. However, Wire clarified that this is not the case.

“The only moral judgement on this album tends to be about me,” he acknowledged. “The song is a multifaceted exploration of my own reliance on the past – about why those years are so indelibly etched in me. It resonates for many people, honestly, but being between 12 and 18, I don’t believe I’ve ever fully shed their imprint on my aesthetic appreciation of music, literature, and film. It’s an inquiry into that.”

“The idea that I had this postcard from Morrissey that said, ‘Get well soon’ and I cherished it, it became a seemingly worthless thing that I imbue with enormous significance. It’s about many different things but centrally about being unable to escape that, and the remarkable comfort and joy it brings. It’s a love letter to my former self, as much as to everything else.”

Bradfield elaborated on how Wire’s rediscovery of the postcard following his mother’s death made it “all the more prescient.”

“She used to send letters and postcards to venues when she knew his favourite band would be performing there,” the frontman recounted. “Whether it was Whitesnake, Rush, or Echo & The Bunnymen, she would send a postcard to the venue saying, ‘Dear Mr McCulloch’ or ‘Dear Mr Morrissey, my son is a big fan of yours, can you please send him a postcard…’”

“When he shared the lyric with me, he explained that it was about the hold this object had over him. Many of Morrissey’s lyrics dealt with illness, or included references to him feeling unwell in the face of life’s demands. Ironically, he returned this postcard saying, ‘Get well soon Nicholas.’ The song centers on the power this inanimate object has over Nick and his emotions, and his struggle to break free from the influence of those times that still resonate within him. Those eras continue to inform him and catch him off guard.”

Bradfield expressed that it felt “beautiful” to paraphrase The Smiths’ ‘I Know It’s Over’ for the lyric “it’s so easy to hate, it takes guts to kind” – and how it was “reminiscent of our feelings during those times in the Valleys.”

“When you’re 16, 17 or 18, music is literally a portal into another world, a lifeline or a spark that transforms you into another person,” he added.

The singer and guitarist dismissed the idea that Wire was commenting on Morrissey’s present character as “over-analysis”, with Wire agreeing that there’s always an element surrounding Manics’ songs.

Each Manics album is famously accompanied by a quote that reflects its character. This time, it’s ‘I am a collection of dismantled almosts’, by Anne Sexton.

“The ‘almosts’ come after that period (of the ‘80s),” Wire explained. “Everything seemed so definite back then. I still cherish everything I did during that time. It’s all about critical thinking – attempting to reevaluate who you are and why you hold onto those things.”

“If everyone could experience the incredible benefits I had growing up – the music around, the parents that I wish everyone could have – it was a typical working-class background but so culturally enriched.”

The Bradfield-penned ‘Brush Strokes Of Reunion’ follows a similar theme, inspired by “an object with power over my emotions.” “It’s about a part of my house that has an oil painting by my mum,” he disclosed. “I would go there to write or read, and since my mother passed away in 1999, that picture has held immense power over me.”

The two other tracks with lyrics by Bradfield are ‘Being Baptised’ (written about a day spent with Allen Toussaint while filming an episode of the BBC’s Songwriter’s Circle in 2011) and ‘Out Of Time Revival’ (“about the malaise of post-lockdown when I was trying to turn every opportunity into a really bad black-and-white B-movie”).

“I thought, ‘Stop searching for meaning in life and answers in all these things’,” he reflected on the latter. “It’s a futile endeavor: writing a song about overanalyzing life and being too pretentious. As Neil Young said, ‘Just find a chord and dig in’. Maintain a steady beat, and you’ll get there.”

Ultimately, that drive to persist is what underpins ‘Critical Thinking,’ serving as a reminder to the band of the essence of making a record. “It helps you realize that maybe you’re talking to yourself more than you realize,” said Bradfield. “It doesn’t always have to lead you to something that feels therapeutic. Writing songs is just a place where you can be yourself. I’ve spent most of my life composing music for Nicky and Richey’s lyrics and that’s a passion I hold dear. There’s a thin line between claiming you’ve discovered the key to life and simply digging in.”

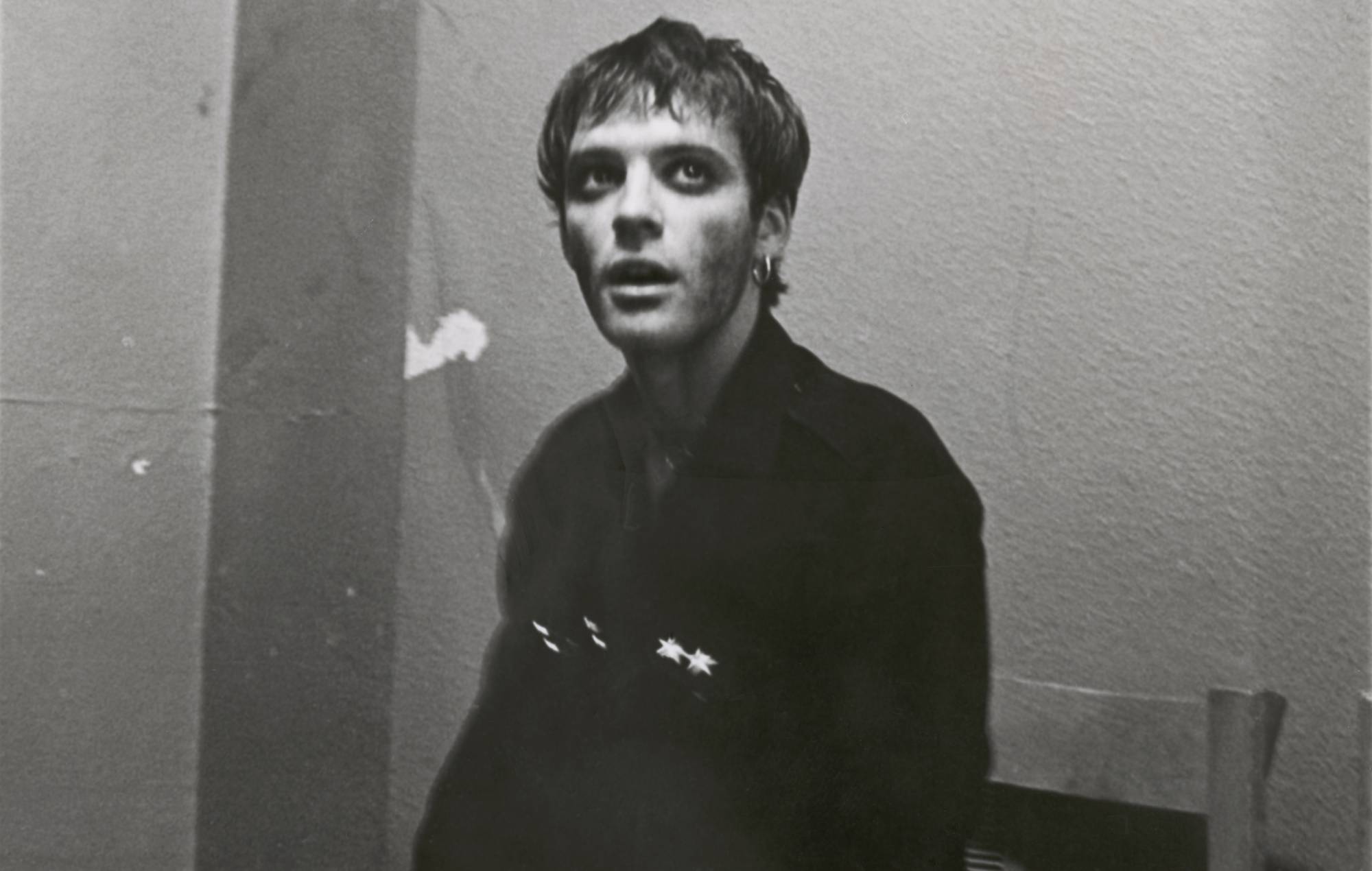

Earlier this month, the band performed two album launch shows at Pryzm in Kingston on February 1 – commemorating 30 years since guitarist, lyricist, and propagandist Richey Edwards disappeared in 1995, ahead of the US promotional tour for their seminal third album ‘The Holy Bible’. He was officially declared dead in 2008, allowing for the settlement of his family’s affairs.

“It never ceases to bewilder me, knowing that he was only 27 when he vanished,” Wire told NME. “He’s been gone for 30 years, and time can be incredibly cruel.”

Acknowledging that such milestones weigh heavily on the band, he continued: “And I know it does for his sister, family, and friends. It’s not merely about Richey the band member. There’s the brother and everything that accompanies that. It almost seems unreal to think that three decades have passed. It’s pretty challenging to fathom.”

Still, Edwards’ influence and ideas resonate throughout their current work. Wire pointed once more to the new album’s title track. “Sometimes you hold yourself back, and I always believed that critical thinking was the power to reject,” he told NME. “Whether that’s consuming works by James Baldwin, J.G. Ballard, Susan Sontag, whatever – it’s that power to say, ‘Do you know what? I’m not sure about this.’”

“It’s that ultimate question. With Richey as well, I continuously feel he’s doing that with his lyrics to ‘Archives Of Pain’ or ‘P.C.P.’ (from 1994’s ‘The Holy Bible’) It’s about the mental training to sit back and reign in those fridge magnet philosophies.”

Bradfield mused: “That’s a very strong motivation for someone like Wire or Richey to write lyrics – to ask, ‘How did we end up here?’ Crafting that song is a much more complex process than it used to be because it’s as easy to challenge your own side’s actions as it is to oppose them.”

Finding their own purpose amidst so much provides a “freedom” for the Manics, as both Bradfield and Wire describe. “You can become completely ensnared and obsessed, whether that’s with critical reception or simply getting airplay, streaming, or your own internal critique,” said Wire. “Time is truly valuable. The one thing I wish for others is to share in the immense luck that we enjoy. When we feel inspired, we just head into the studio. We are skilled enough now, whether alone or together, to produce something worthwhile.”

“It’s crucial that we still feel that we possess that energy,” he added.

The time since ‘The Ultra Vivid Lament’ saw the band revisit two of their more divisive albums – reissuing the political ‘Know Your Enemy’ and the personal synth-pop of ‘Lifeblood’ to celebrate their 20th anniversaries. Somewhere in between the fury and introspection of those records, Wire admitted they found inspiration for ‘Critical Thinking’ (“It resembles a hybrid of both of those – perhaps it had more impact than I recognized”) with the sonic shifts of ‘Lifeblood’ and 2014’s Berlin and kraut-rock-inspired ‘Futurology’ igniting ambitions for their next LP.

“It was illuminating to revisit ‘Lifeblood’ – an album that I was unsure about for quite some time, apart from a few tracks,” reflected Bradfield. “Now, I view it as a truly successful experiment. It’s a bit disconcerting that it took me this long to realize that fact. It highlights that in terms of processing information on a sub-intellectual level, I’m still lagging behind. It took years for me to appreciate that ‘Lifeblood’ was a quality record. I’m not saying I want to create a record like ‘Lifeblood’, but dissociating oneself from emotion can sometimes be beneficial.”

“We were discussing the other day, and our sole current interest is to go abroad to record. We would love to keep things cold and European. I’m not saying that this will lead to ‘Futurology’ part two, but that’s what’s occupying our minds. We haven’t even released this record yet, so the fact that we’re contemplating our next steps is quite encouraging.”

Wire considered some of his bandmate’s ideas about new producers for their next album in Hamburg, adding: “James possesses this spontaneous nature of bursts of ideas that need to be harnessed quickly or they’ll dissipate.”

“‘Futurology’ is among the best Manics albums and has withstood the test of time. In my view, ‘Lifeblood’ and ‘Futurology’ complement each other regarding their smoothness. I could certainly envision us pursuing that direction.”

“I haven’t crafted many lyrics lately because it’s advisable to take a break from the album you’ve just finished and avoid redundancy. This one is intended for the dark night of the soul, but I’m confident the next will differ from that. Whether it’s broader or takes a more macro perspective. We shall see.”

Wire added: “There’s always a song waiting to be written. Much of it now comes down to willpower and seizing that flash of inspiration. When such a moment strikes, you must act quickly or it evaporates.”

Noting how they’ve moved beyond the midpoint of their career, Bradfield asserted that the band has become “hard-nosed” about their direction – yet they still found reasons to persist.

“Once you understand that you are closer to the end than the beginning, that really sharpens your focus,” he stated. “It’s pure math: this is our 15th album, and there’s no way we can produce another 15 records. You just wish to continue that process until you can’t.”

“If we’re not interested in doing something, then we won’t, but if we still enjoy each other’s company after all these years, and don’t wish to throttle each other, then it’s undoubtedly worth continuing.”

Check back at NME soon for more of our interview with Manic Street Preachers.

‘Critical Thinking’ is out now, with the Manics starting a UK headline tour in May. Visit here for tickets and more information.

https://www.nme.com/news/music/manic-street-preachers-interview-critical-thinking-dear-stephen-lyrics-meaning-richey-edwards-future-3838170?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=manic-street-preachers-interview-critical-thinking-dear-stephen-lyrics-meaning-richey-edwards-future